A magnitude 3.0 earthquake rattled the remote Aleutian Islands on November 27, 2025, striking just six miles south of the village of Akutan at 8:13:54 a.m. Alaska Standard Time. Though minor by global standards, the tremor occurred in one of the most geologically restless regions on Earth — a place where the Pacific Plate dives beneath the North American Plate with relentless force. No injuries or damage were reported, but the event added another data point to a pattern that scientists have been tracking for decades: in the Aleutians, even small quakes are part of a much larger story.

The Aleutian Machine: Why Small Quakes Matter Here

What makes this quake more than just a footnote is where it happened. Akutan sits on an island that’s essentially a scar on the Earth’s crust — the edge of the Alaska Earthquake Center’s most intensely monitored zone. The Alaska Earthquake Center, based in Fairbanks, tracks every tremor in the state, but the Aleutian Arc is its priority. Here, three types of earthquakes happen simultaneously: massive megathrust events at the plate boundary, intermediate quakes deep within the sinking Pacific Plate (the Wadati-Benioff Zone), and shallow, often volcanic, rumbles from the crust above.

This particular quake, recorded at 19.9 miles deep, fell squarely in the category of crustal faulting — likely tied to the stresses of the overriding North American Plate. It wasn’t a megathrust event like the 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake, nor was it a deep slab rupture like the 2014 M7.9 Little Sitkin earthquake. But it was typical. In a region that sees hundreds of quakes every year, a magnitude 3.0 event is like a sneeze — noticeable, but not alarming. Still, in the Aleutians, sneezes often come in clusters.

A Chain of Rumbles: The 24-Hour Sequence

Here’s the twist: within 24 hours, the ground didn’t stop shaking. At 12:52 a.m. on November 28, a magnitude 3.3 quake struck 47 miles southeast of Akutan, near coordinates 53.54°N, 165.22°W. Then came two more: a 3.0 near Makushin Volcano at 8:31 p.m. that same day, and a shockingly shallow 2.3 just south of Mt. Recheshnoi at 11:48 p.m. — at a depth of just 0.6 miles. That last one? It was practically at the surface.

These aren’t random. The Alaska Earthquake Center has documented similar swarms before — especially near active volcanic centers like Akutan, Makushin, and Recheshnoi. The shallow quakes suggest magma movement or gas release beneath the surface. The deeper ones? They’re the slow grind of tectonic plates adjusting. When they happen together, it’s a sign the system is under pressure.

"We’ve seen this pattern before," said Dr. Lena Voss, a geophysicist with the Alaska Earthquake Center who has studied the region for 18 years. "A small tremor near a volcano, followed by others nearby — it’s not always a precursor to eruption, but it’s a signal we pay attention to. The ground is talking. We just need to listen carefully."

Why No One Felt It — and Why That’s Important

Akutan’s population hovers around 1,000 people. Most homes are built to withstand quakes. The 1996 M7.0 event nearby caused structural damage, so modern construction here is resilient. This 3.0 quake? At 20 miles deep, the energy dissipated before reaching the surface. Residents likely didn’t feel anything. Some might have noticed a slight vibration if they were sitting still. But no alarms rang. No buildings cracked.

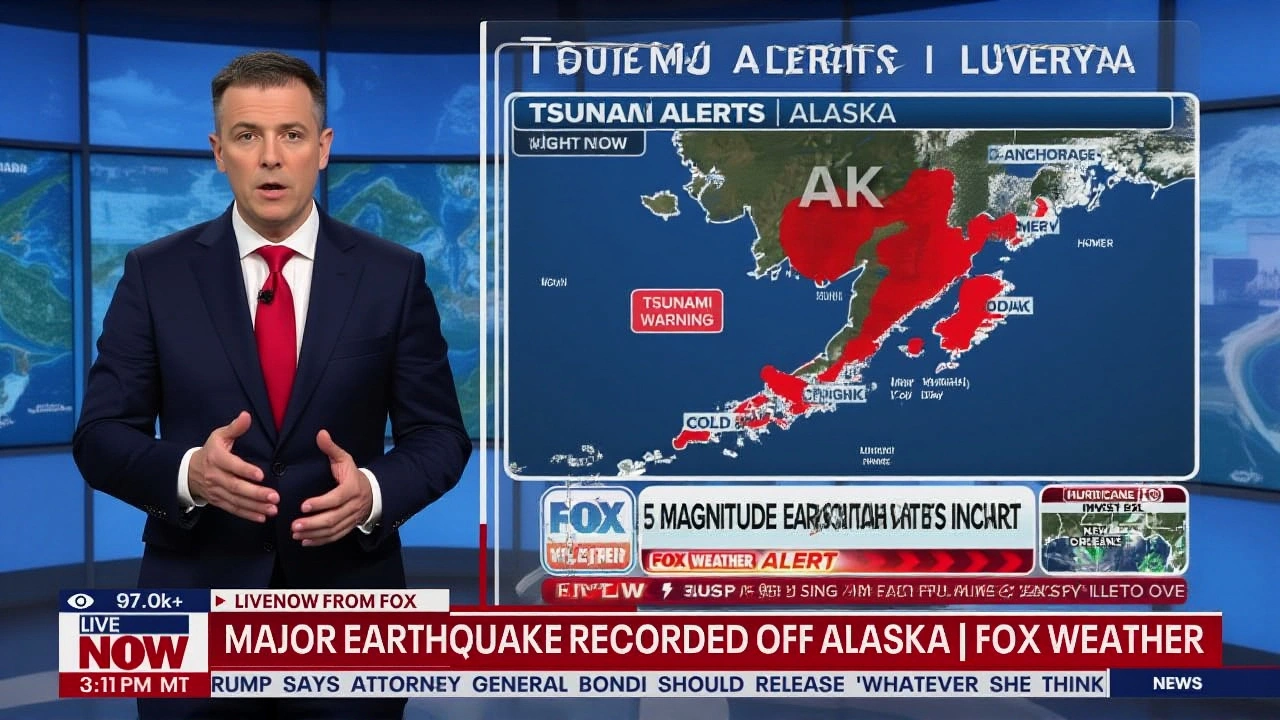

That’s actually good news. In a region where quakes of magnitude 7 or higher strike every 10–15 years, a 3.0 is a quiet reminder that the system is functioning as expected. The real danger isn’t the small ones — it’s the big ones that come without warning. The 1957 M8.6 earthquake near the Andreanof Islands? It generated a tsunami that wiped out villages across the Pacific.

What Comes Next? Monitoring in Real Time

The Alaska Earthquake Center has not yet reviewed the November 27 event with a seismologist — meaning it’s still preliminary. But their network of 120 seismic stations across Alaska is already analyzing the data. They’re watching for two things: a pattern of aftershocks in the same area, or a new cluster forming elsewhere along the arc.

Historically, swarms like this one have sometimes preceded larger events — but more often, they just fizzle out. The 2019 swarm near Cold Bay, for example, included over 150 quakes over three weeks. No major quake followed. Still, every cluster is logged, mapped, and compared against past behavior.

"We’re not predicting earthquakes," said Dr. Voss. "We’re mapping stress. We’re learning how the crust breathes."

The Bigger Picture: A Fault Line That Shapes a Continent

The Aleutian Arc isn’t just Alaska’s problem. It’s part of the Pacific Ring of Fire — a 25,000-mile horseshoe of seismic and volcanic activity that circles the Pacific Ocean. The subduction here is among the fastest on Earth, at nearly 7 inches per year. That’s why the islands are so volcanic, so fractured, and so prone to quakes.

The 2014 Little Sitkin earthquake, at 100 miles deep, remains the largest intermediate-depth quake ever recorded in the region. It shook the ground from Kodiak to Unalaska. But the small quakes — like the one near Akutan — are the daily rhythm of a planet that never sleeps.

Frequently Asked Questions

How common are earthquakes near Akutan, Alaska?

Earthquakes near Akutan are extremely common — the region records 50–100 detectable quakes annually, mostly between magnitude 2.0 and 4.0. The Alaska Earthquake Center logs dozens of smaller tremors daily across the Aleutians. A magnitude 3.0 event like the one on November 27, 2025, is routine and typically goes unnoticed by residents.

Could this earthquake trigger a larger one or volcanic eruption?

While possible, it’s unlikely. The November 27 quake was too small and too deep to significantly alter stress on major fault lines. Volcanic eruptions require magma movement, which can cause shallow swarms — but no signs of rising magma have been detected near Akutan. The Alaska Earthquake Center continues to monitor gas emissions and ground deformation, but no alerts have been issued.

Why did the Alaska Earthquake Center not review the event yet?

The Alaska Earthquake Center processes hundreds of events daily. Only events above magnitude 4.0, those near populated areas, or those with unusual patterns are reviewed by seismologists immediately. The November 27 quake was classified as preliminary because it was small, deep, and followed a known pattern. Review typically happens within 48–72 hours.

What’s the difference between the Wadati-Benioff Zone and shallow earthquakes in the Aleutians?

The Wadati-Benioff Zone refers to earthquakes occurring deep within the subducting Pacific Plate, typically between 30 and 150 miles down. These are often larger and more powerful. Shallow earthquakes, like the 2.3 near Mt. Recheshnoi, happen within 5 miles of the surface and are usually linked to volcanic activity or local crustal fractures. The Akutan quake was in between — shallow enough to be crustal, but too deep to be volcanic.

How does this compare to other recent seismic activity in Alaska?

In the past month, Alaska recorded 17 quakes above magnitude 4.0, including a 4.7 near Chignik on November 15 and a 4.5 near Unalaska on November 22. The Akutan event was one of dozens of minor tremors. While not unusual, the clustering of four events within 24 hours near the eastern Aleutians is notable — similar to patterns seen in 2018 and 2021, both of which ended without major events.

Is Akutan at risk from tsunamis due to earthquakes?

Yes — but not from this event. Tsunamis require megathrust earthquakes (magnitude 7.5+) that displace the seafloor vertically. Akutan sits on the edge of a zone that has produced such events, like the 1957 M8.6 quake. The Alaska Earthquake Center maintains tsunami warning systems here, and residents are trained to evacuate if a large quake is felt. The November 27 event was far too small to trigger one.